Philip Moss presents a large-scale exhibition of new and recent work, representing a range of inspiration that has impacted his work to date.

When Moss was a child, he spent two and a half years in hospital. He was four when he went in, and six and a half when he came out. Fifty-five years later, he is making the most personal work of his life, and he has gone back to the trauma of that formative experience.

Moss has lived in Donegal for over 30 years, having moved from London where he worked with Auerbach, Bacon and Freud. His art practice has an edge, both social and political, sometimes this is subtle, often more direct. His paintings have been described as being ‘tinged with a rare, almost spiritual quality.’ For him, action and painting are one in the same – they are purely matters of conscience.

Curated by Jeremy Fitz Howard.

Exhibition essay by Cristín Leach and textual responses by Emily Cooper.

Words on Canvas by Cristín Leach is available to read on RTÉ Culture

Exhibition Response (Extract)

by Emily Cooper

Introduction

There is a pleasure in writing about art that wears its influences on its sleeves. Viewing Philip Moss’s work is not a simple experience; there are threads to pull on, curtains to pull back, and ideas, often tricky, to wrestle with. In writing these poems, I spent time reading around the paintings. I watched youtube videos of artists’ studios, read interviews with their assistants, and searched artworks referenced overtly and discreetly. I was also very lucky to have Moss himself to hand, always happy to point out what something is or to elaborate on his process, something rare and exciting to have access to. What I have written does not explain the work, rather it is the product of being introduced to the possibilities of the paintings and what they led me to on a particular day. It is wonderful to think that had I encountered them at a separate time, another year or season, I might have written something completely different. I hope that through viewing the exhibition, either in person or through this publication, and meeting the corresponding poems, you might find something you can approach again and again with fresh eyes and ears.

House by the Railroad (Edward Hooper)

Ed is sitting in the front room with his feet on top of the coal stove. He has just had a fight with Jo about going down the three flights of stairs to get more fuel and she has locked herself in the kitchen. She is making beef stew from a can. He is fucking sick of beef stew from a can. He begins to think about balustrades. The symmetry of rows and rows of columns holding something up. He scratches lines into the arm of the armchair, scoring the faux leather, strikes them through.

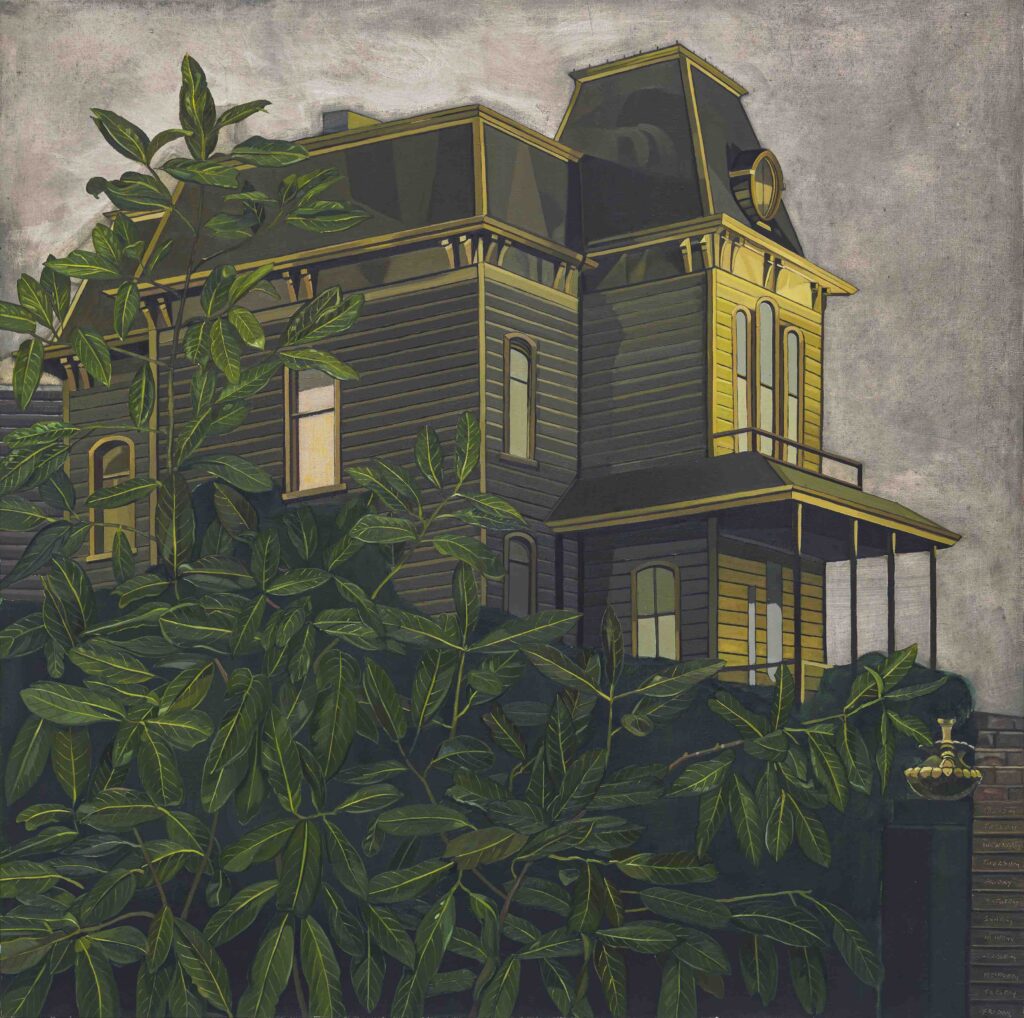

Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock)

Alfred Hitchcock is sitting by the pool. Someone has folded up the day’s newspapers on the table, the ink looks wet in the sunlight. He doesn’t want to dirty his white dressing gown. He has tied it tight below his belly, the sour sweat of last night’s champagne has touched the cotton but is eclipsed by the clean smell of washing powder. His eggs arrive and he sets down his coffee. A small dog barks somewhere inside.

Psychobarn (Cornelia Parker)

Cornelia is speeding past the prison on her way to the supermarket. She notices the cracks in the prison wall and resolves to come back and photograph them on another day. On her way around the aisles she thinks about barns, big and red, dropped almost at random in the American countryside. She thinks again about the danger of lead poisoning, looks down at her hands on the trolly and notices the splits around her fingernails, rags. On her way home from the supermarket she forgets about the cracks on the prison wall, instead counting how many of the postwar houses have applied new conservatories around the front door. Fortresses, or not quite.

Title (Philip Moss)

Philip is on the phone with his son. He walks around the back of the house where the reception is better and looks through the window of his studio. Inside the paintings are stacked up against the walls. He tells his son about an idea he has for a texture, the type of paint he needs to find. He asks what his son will have for dinner, they are eating late tonight because they ran out of butter and Sara has had to nip to the shop. Thank god for the late evenings, and the excess of light. He needs to say goodbye quickly as he’s heard tyres on the drive, walks around the front to help.

This Poem (Emily Cooper)

Sitting at the table in the upstairs living room, Emily is calling down to her boyfriend in the kitchen to make her a gin fizz. She is almost finished a project and she doesn’t want to stop. The table is covered in a bedsheet and cluttered by books she has only momentarily flicked through; books on artists and literary journals that she has skipped through only to read the work by people she knows. She thinks about dumping the dead flowers on the mantlepiece, but knows she will leave them for another day. Her gin fizz arrives and she drinks it quickly as she types, ready to be finished if she can manage it tonight

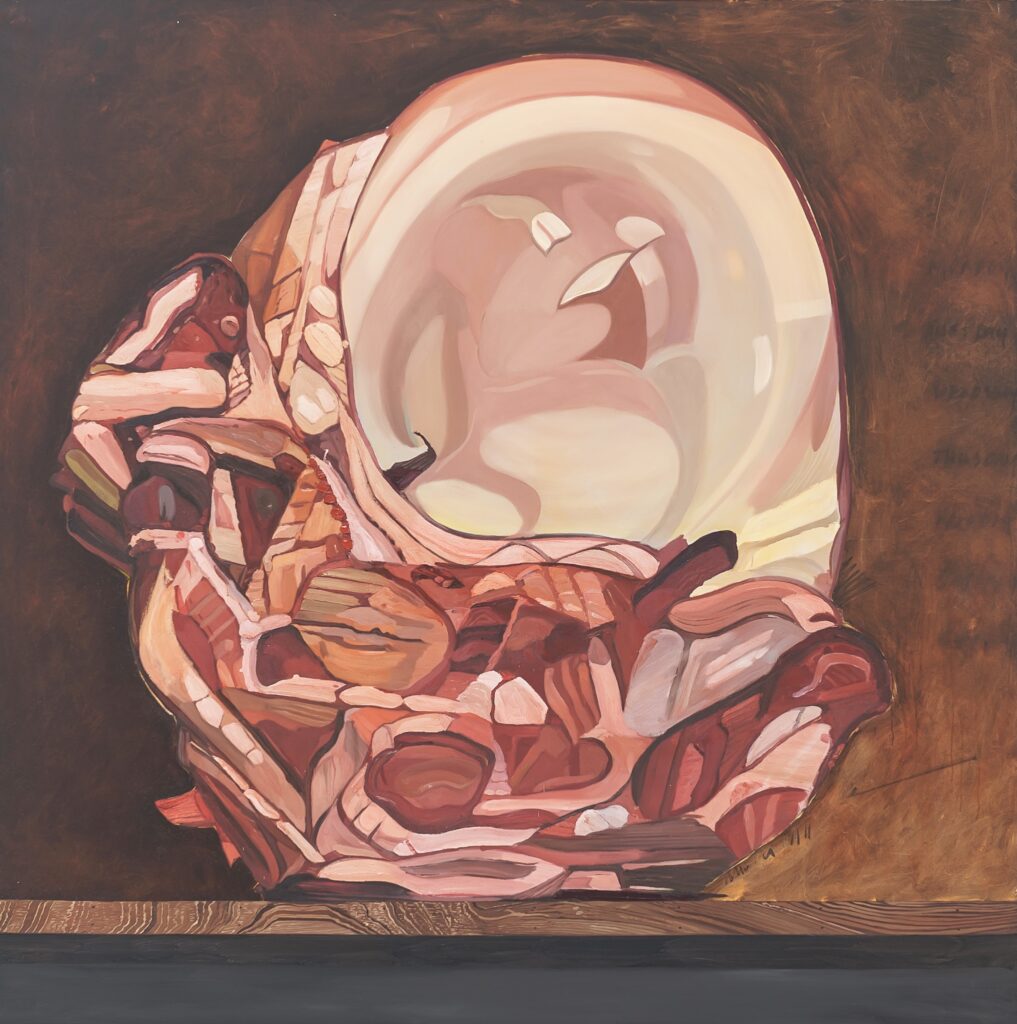

Flesh and Bones

Underneath the many layers

Cutaneous, subcutaneous

The striations of muscles

From below the cold yellow fat

Emerge the bones

A bone can be a statue

Not so far away from marble

As to deny a relationship

A kinship of mineralisation

Slow cousins of deposition

When you look at a body

Do you see the skeleton

In the way that a sculptor

Sees the sculpture in the rock

A pygmalion nod?

It was only after many years

Of myth making that Galatea

Got her name. Born from stone

Milky white and already

Submissive, ready to love

The softness of flesh

Alerts us to the possibilities

Of rot. The smell of death

It multifarious. Sometimes

Sweet, sometimes not

Only in a body that is

Pared back by wounds

Or openings, perhaps a widened

Jaw, can we glimpse white –

An alabastor of permanence

Étant Donnés – Philip Moss

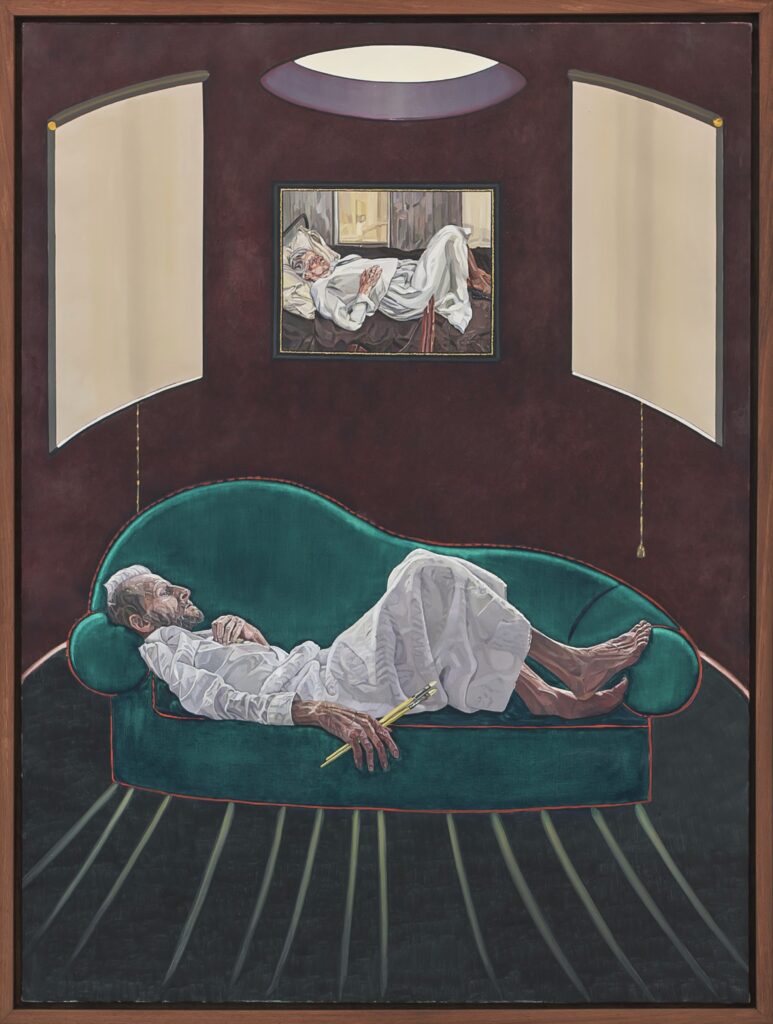

Learn to Sew

On admiring the curtains in my friend’s mother’s house

she explained that these were her inheritance.

Chests of fabric saved over years. Accumulated

from Liberty sales and long closed haberdasheries.

Each curtain had been constructed by hand and machine.

Ticking thick and weights, double lined for privacy.

It is such a luxury, we all concur, to shut out the world,

to draw them closed, black out the light momentarily.

Solitude is so very difficult to hold onto. Perhaps

if I were to start it all again I would begin here, with the fabric

on my lap, pinch and sew until I have a cover to cover it all

from ceiling to floor, puddles of linen, velvet, printed cotton.

Had we never tried to peek, we wouldn’t have seen Maria Martin,

headless and holding up Teeny’s arm.

I read that Lucian Freud wore a cravat in bed

David Dawson is searching Brick Lane for cotton sheets.

Each one starched and bleached and starched and bleached

of their fluids and stains, hotel guests rubbing themselves

free of macassar and perfume. Special lotions bought

in boutiques to wear on their yearly trip up to London.

Dawson has brought them back to the flat, stuffed deep

into black bin bags. Every morning Lucian pulls a length out

rips it to size, the threads splitting, nip nip nip

only to catch on the thickened edge. He tucks

his selection into his trousers and begins to paint.

Each day before the sitter arrives, after boiling the coffee

in the studio kitchenette, Dawson counts the tubes.

The cupboard is a cornucopia of paint, replenished

silently in shades that can be found on native British birds

cremnitz white procured ashen-faced and underhand.

How close to death does one need to be to wear a shroud?

I think of Penelope at the loom, weaving by day, picking

by night. Lying down is an act of submission, rage rage –

at the end of each day Lucian would drop the apron

to the ground forming waves of memories, a cotton tide.